In a conversation with Karen White, the incredible and extremely skilled co-founder of the African American History Association of Fauquier Country, I learned how she got into the work she currently finds herself in. 35 years ago, she took her young daughter into the New Leaf book store in Warrenton, looking for books that looked like herself and her children. The store owner directed her to where she could find what she was looking for, and there she stumbled upon a book that would start her down a journey that she’s still on. As she thumbed through the selection of books, she stumbled upon an abstract of birth records, by Joan Peters. Looking through this book, she found her grandmother’s two sisters. Thus began the deep and winding journey into her family’s history.

In the genealogical work that I’ve been doing for the Preserve so far, I’ve learned a couple of things. Because of the composition of the United States at that time, and specifically Virginia, I’ve had to be very creative when looking for information about African American people. Primarily because legally, African Americans were viewed and legislated as property.

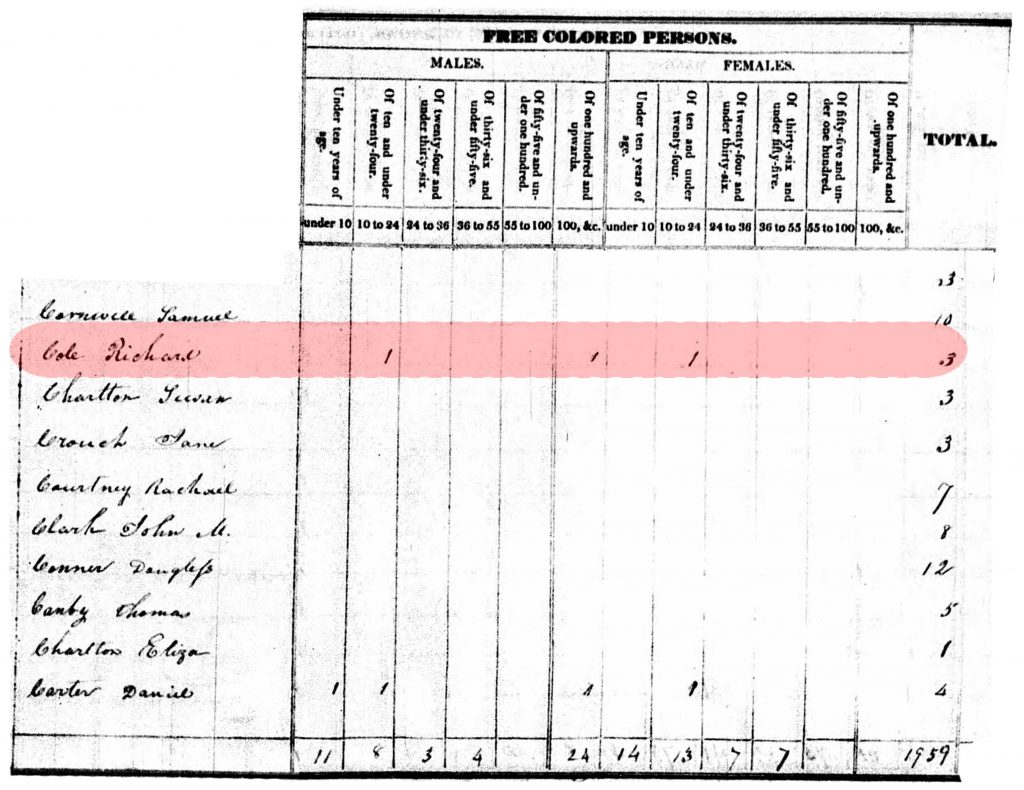

For example, one of my research subjects, the Cole Family appears on the 1830 census as free people, but don’t show up on any other previous census logs. If they were enslaved, they were not logged on their own, but essentially in the inventory of a white person. Meaning that a lot of my information ends up coming from various receipts, deeds, letters, and other mediums where these people are mentioned offhandedly.

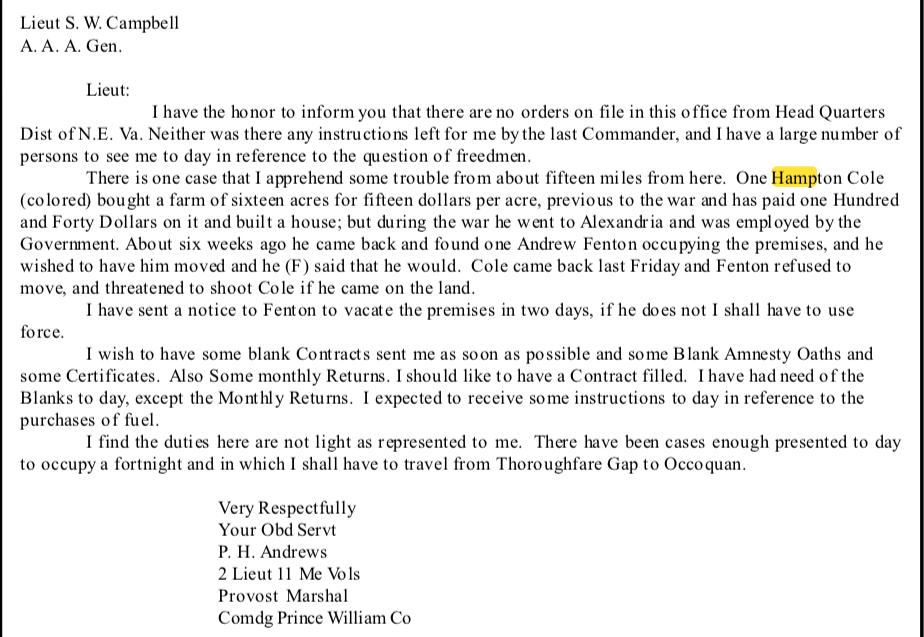

Even after the United States official end to chattel enslavement, there were people in my home state of Texas, that did not know that they’d been released from enslavement until 2 years later, on the day now known as Juneteenth. Because emotions, personal opinions and ideology cannot be legislated to change, a white male enslaver by the name of Andrew Fenton, squats in the home of Hampton Cole, a free black man who was working for the Confederacy.

When Cole returns home after the war, Fenton threatens to shoot him if he dares come back and try and reclaim the land he bought and the house he built. We only know this because of correspondence we see sent from one Confederate lieutenant to his superior on Cole’s behalf.

As my conversation with Ms. White continued, she asserted that idea that African Americans cannot ever be successful in their own genealogical work is a myth. She just had to learn where and how to look. Because she only found her grandmother’s sisters and not her grandmother herself in the abstract, she went to the foreword and found out that Virginia did not have to record births after 1896 and didn’t start again until 1912 or 1913. Her grandmother was born in 1896, explaining why she did not appear in the abstract. She went to family gatherings and started talking to older members and collecting information as well. It was actually at the 80th birthday of a family member that she met the co-founder, because they shared that relative.

Decades later, the work that began with finding out about their personal histories, provided opportunities for other Black people to find out about their own families, and furthermore, for this Black person to discover details about a family she doesn’t even belong to. Ms. White explains that, “any group of people that could survived that they had survived needed to be put on up pedestals, and that we need to learn how to follow in their footsteps of having that strength and endurance. So with that, I just felt like I should share this information because it’s not just my family, but everybody’s family and everybody’s family is equally important.”

Although the words are not my own, the sentiment expressed is definitely one that I hold close as I continue this work. Affirming the inherent value and worth of the people that I am trying to bring to life for those who interact with the Preserve now and in the future. The more we are able to fill in the gaps when it comes to the history of the Preserve, the more vibrant, inclusive, and beautiful our future will be.