Ron Crawford has lived in the Roanoke Valley for more than 75 years, and Read Mountain has always been in his sights. “Every home I’ve lived in seemed to focus on it,” he says. “I guess I’ve always considered it my mountain.”

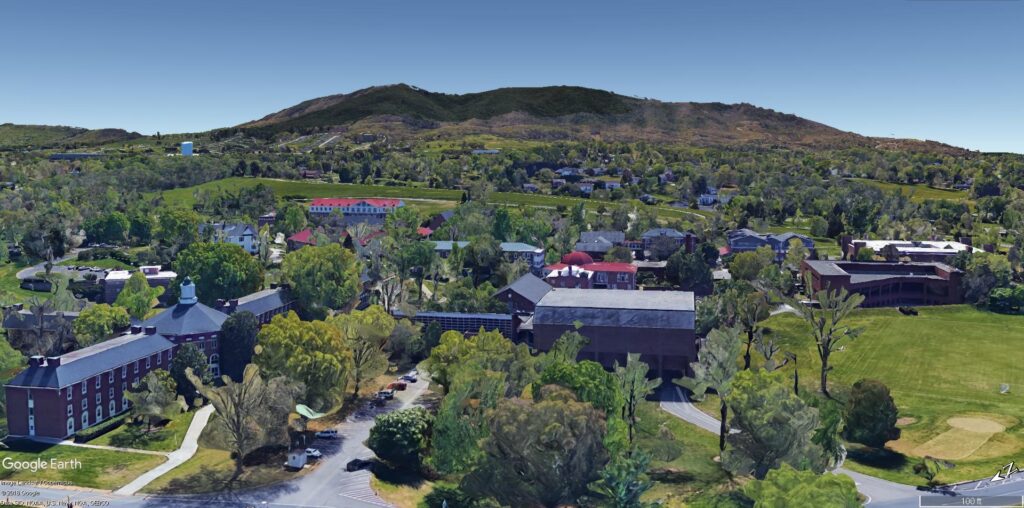

Crawford remembers the first time he climbed it, at the age of 12 in 1948. He also remembers when he retired in 1996 and built a house 800 feet below the ridgeline. That’s when he noticed that Read Mountain was the only mountain in the area with virtually no man-made structures on its upper slopes and ridges, and when he first thought that the mountaintop might need saving.

“Back in the 1930s the Civilian Conservation Corps had built a trail along the ridgeline,” he says. “My thinking was that maybe we could call it a historic trail and preserve a 1,000-foot-wide corridor along it. But then the greenway coordinator at the time, Liz Belcher, came out to see it and she said, ‘Think bigger.’ That was all I needed.”

Crawford founded a citizen’s group in 2000, the Read Mountain Alliance, and started a fundraising effort. “We had hikeathons with 45 to 50 people each time, we made presentations to city and conservation groups. We even made a video and gave it out to help people understand the importance of the mountain. We knocked on a lot of doors.”

The work started to pay off in 2005, when real estate company Fralin and Waldron and landowner Al Durham made the first easement and land donations, totaling 243 acres. Alliance partners in the project include the Blue Ridge Land Conservancy (BLRC), the Roanoke County Greenway Commission, Roanoke County Parks and Recreation and Virginia Outdoors Foundation.

A grant from VOF’s Forest Core Fund in 2019 added 304 acres and protected the addition with an open-space easement deeded to VOF. Another grant, this time from VOF’s Preservation Trust Fund, will help the county add another 56 acres. The acquisition of the additional land and the easement to protect it are being finalized.

Greenway coordinator Frank Maguire stresses the importance that public-private partnerships have had in pursuing a shared vision of keeping the mountaintop whole. Private landowners, he states, “are setting a good example of what’s possible” in conservation.

Maguire is talking about the Bradshaws, John and Matilda Holland. Matilda grew up on the Andrews family farm on the northern slope of the mountain and has many memories of climbing trees in the apple orchard with her sisters. When it came time to sell, the family wanted Roanoke County to have the property, knowing that it would be protected by an easement and added to the preserve, nearly doubling it in size.

“It’s very special to us,” she states. “We could see other mountaintops with pin cushions all across for cellular towers. I know that the towers are necessary, but we were excited to keep our mountaintop pristine.”

Now both the north and south slopes of the mountain and the ridgeline are protected, but Crawford and the Alliance show no signs of slowing down. The group raised $90,000 toward the acquisition of the 56-acre addition and are setting to work on a master plan for a new trail head and trails on that side of the mountain.

“It’s all about getting conversations started and keeping them going,” Crawford says. “But I didn’t have to convince anybody; everybody I talked to saw this mountain as a resource.”

Could you please make sure that when referencing the Forest CORE fund in articles, you make clear that the money comes from a “mitigation” agreement Mountain Valley Pipeline made with the state of Virginia for the trees removed for construction and pipeline right-of-way that will remain permanently cleared. Further explain that these were all privately owned lands.

Comments are closed.