With the warmer, wet weather recently, there is no shortage of activity happening in the Preserve as more plant and animal species begin to emerge. Amphibians, in particular, are more visible and vocal as they search for true love. We will be focusing on the lifecycle and behavior of the spotted salamander (Ambystoma maculatum) for this week’s #sciencesaturday species. The word “amphibian” means two lives (Amphi = both; bios = life, in Greek). These native salamanders are cold-blooded, have smooth and slimy skin, and live a transitory double life moving from water to dry land as they mature.

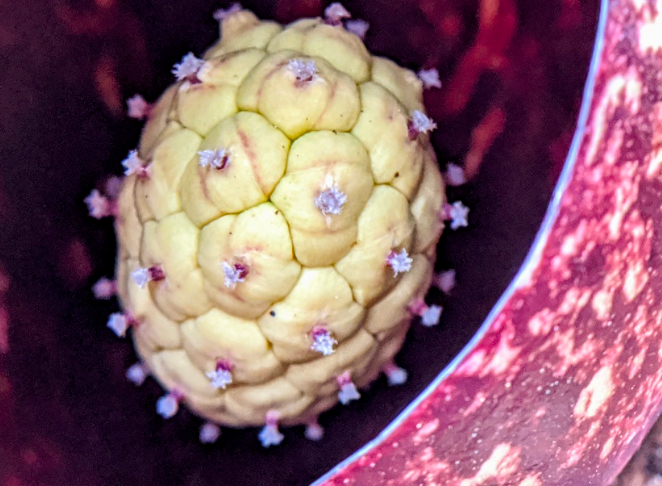

Their life cycle begins as an egg underwater. Females lay between 2-4 clutches of eggs, each containing up to 250 eggs, in vernal pools, wetlands, or slow moving bodies of water. These eggs, which look like pearls or tapioca balls, are further protected by an additional layer of semi-transparent gel or film to prevent the eggs from drying out. The eggs also contain single-celled green algae, which consume the carbon dioxide produced by the embryos and turns it into oxygen. The eggs hatch after 20-60 days.

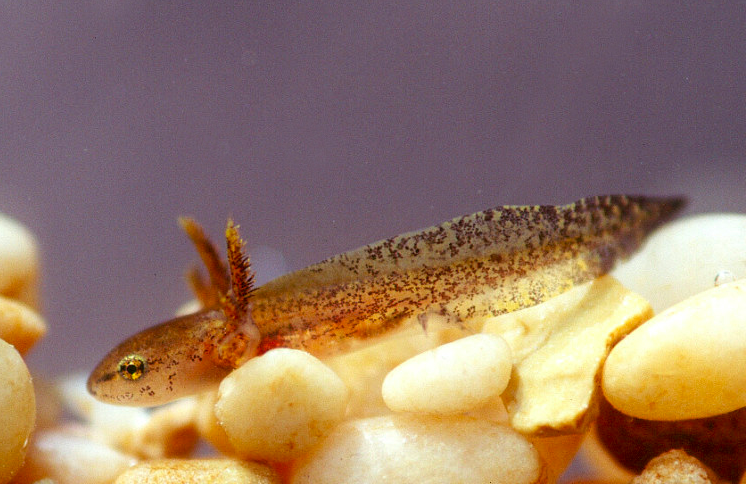

Survival to the larval stage is very low, with less than 15% of the hundreds of eggs successfully hatching to beat the odds of predation and desiccation. As larva, spotted salamanders hatch with two front legs and external feathery gills. They will eat any small aquatic invertebrates that share their pool, including other salamander larva if they are overcrowded. Once they undergo the final stage of metamorphosis and develop lungs and four strong legs after two to four months, the juveniles are ready to leave the water. They transition from the aquatic habitat into a terrestrial ecosystem, finding a home under rocks and logs on the forest floor, often less than 100 meters from their pool. A fossorial species and active after dark, they only emerge from underground to breed or hunt. They prefer eating small insects, using their sight and smell, catching prey with their sticky tongue.

Adults can grow up to 10 inches long and have a row of yellow or orange spots along their stout blue-black body. These markings warn predators that spotted salamanders are poisonous and can release a foul-tasting toxin from glands on their backs and tails. After two to seven years, juveniles reach sexual maturity.

They join the annual migration back to the very same home pools they hatched from (if possible) at night during the first warm rains of late winter. Males will arrive first, and deposit spermatophores packets along the bottom, which the slower moving and larger females will take up into their reproductive tracts to fertilize their eggs. Once the females lay their eggs, they head back to their burrow (following the exact same route they used to arrive) and abandon the eggs, providing no more maternal care. Adults can live up to 30 years in the wild!

Because salamanders, like most other amphibians, breathe and absorb water through their very thin skin, it is important to be very careful around them. They are incredibly sensitive to any type of pollutants or chemicals in the water, but especially ones we have on our hands like sunscreen or hand sanitizer. Spotted salamanders can dry out quickly if handled improperly or their homes are frequently disturbed. Please be mindful that intentional physical interaction with wildlife while at the Preserve must be under the watchful expertise and supervision of a staff member. When you are out hiking by yourself or with friends, take a picture of the amphibians your find and upload it to our iNaturalist project!